Showcasing Peranakan dress style to the world

“THE recent 68th Miss Universe competition saw our country’s representative, Shweta Sekhon, showcasing a stunning Peranakan-themed national costume,” a friend calls me up excitedly soon after our homegrown designer’s unique creation was spotted on stage.

A keen enthusiast of the popular annual event, he owns a vast collection of photographs and other memorabilia featuring beauty queens who have represented our country in the past.

His exuberance is understandable as the Miss Universe Malaysia competition is considered the longest running and most widely followed beauty pageant here.

Our local version of the international beauty extravaganza was established in 1964 and the first winner of the pageant was Angela Filmer from Selangor. Since then, the Miss Universe Malaysia competition has continued to grow in strength annually.

Despite the pageant’s long history with countless numbers of stunning gowns already paraded, this year’s edition proved to be especially meaningful as Miss Universe Malaysia 2019 was wearing a costume inspired by Malaysia’s multicultural character and diversity when she went on stage with her fellow contestants from the world over for the coveted Miss Universe crown in Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States on Dec 8, 2019.

Before our conversation comes to an end, my friend provides more details about the costume, saying that it bears a combination of elements from Malay, Chinese and Peranakan cultures.

HERITAGE INTERPRETATIONS

“The dress is primarily made of songket, which is then meticulously embroidered with elaborate beadwork. Completing the outfit is a golden cape that bears a resemblance to the traditional wedding costume worn by Peranakan brides,” he elaborates.

His comments strike a chord. In recent years, pageant costumes had become more and more creative, ranging from an outstanding nasi lemak theme to a design similar to those found on traditional Malay boats.

These elaborate, larger-than-life interpretations of our rich heritage should be lauded. Like past entries, this year’s Peranakan tribute successfully ticked all the right boxes.

With my interest piqued, I head for my study to seek out reading materials and photographs to shed light on the origins of the Peranakan.

I wanted to learn how the Straits Chinese Baba men and Nyonya women dressing styles managed to evolve so seamlessly to the point where their position as an integral part of this enduring heritage was achieved.

Although the British ruled Straits Settlements, formed in 1826, comprised Penang, Melaka and Singapore, it is widely accepted that Melaka, due to its long history that dates back to the 15th century, is the original centre of Peranakan culture.

The Chinese traders and merchants who arrived in the Malay Archipelago before the 19th century almost completely comprised men.

They were primarily from the Hokkien dialect group, while a small minority spoke Hakka, Cantonese, Teochew and Hainanese. With their movement across the seas dictated by the monsoons, it was often necessary to spend up to six months in their port of call.

NEW ETHNIC GROUP

That relatively long duration resulted in loneliness and eventual intermarriages with local women. During those early days, those nuptials and the predominantly Malay social environment became crucial factors that gave rise to an entirely new ethnic group that later became known as the Peranakan.

Although this term is most commonly used to refer to the Straits Chinese, or Baba and Nyonya, there are also other comparatively smaller Peranakan communities, such as Indian Hindu or Chitty Peranakan, Arab and Indian-Muslim Peranakan and Eurasian Peranakan of Portuguese and Asian ancestry as well.

It is not clear when the Peranakan identity first developed, but one thing that’s certain is that the acculturation of the early immigrants preceded it. This is especially true for the Straits Chinese as the multi-fold increase in the number of immigrants from China during the 19th century and their subsequent intermarriages caused an increase in population of this unique ethnic group.

While the Straits Chinese retained most of their ethnic and religious origins like ancestor worship and religious observance, other factors like dressing style saw a gradual and close assimilation with Malay culture.

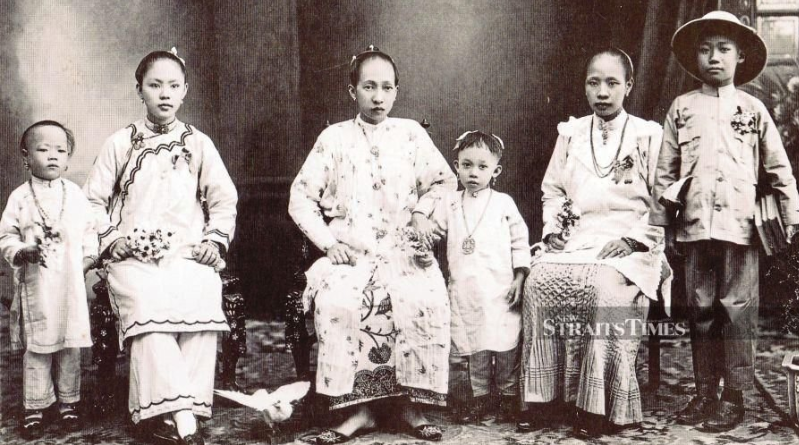

The Peranakan wore different types of clothing depending on their occupation and standing in society. The clothes they wore were different compared with newly arrived Chinese immigrants.

CONTRASTING STYLES

Known as sinkheks, these new arrivals, predominantly male, made their living as labourers. As menial workers, they wore short baggy trousers secured around the waist with a piece of string and had straw sandals on their feet.

On the other hand, wealthier merchants, including Peranakan, could afford better clothes like outer robes or coats worn over comfortable loose-fitting shirts, long, baggy trousers, thick-soled shoes and Western-styled hats or traditional skullcaps.

Sinkheks of the opposite gender working as domestic help usually wore the samfoo, a blouse and trousers combination. Later, women immigrant arrivals opted for long blouses with full-length wide sleeves matched with skirts made of the same material.

Despite the marked influx of sinkheks during the early 20th century, only a miniscule percentage who exhibited excellent business acumen and great potential in helping to expand the family business were given permission by established Peranakan to marry their daughters.

Preference, however, was always given to suitors from the same social standing, quite often with maternal first cousins, in order to preserve and expand wealth within the family unit.

During those rare matrilocal form of Straits Chinese marriages, the sinkhek groom had to forgo his own surname and he, together with his future offspring, would take on his wife’s family name.

World War 2 and the near complete decimation of wealth and opulent lifestyles, compounded with rapid modernisation, brought this custom to an end.

WESTERN INCLINATION

Towards the end of the 19th century, male Peranakan dressing styles began to closely mimic those worn by high-ranking colonial officials and affluent European entrepreneurs with whom they socialised regularly to gain support for their businesses.

The only time Babas wore something with local flavour was at home, where kain pelikat was the casual attire of choice.

This type of cotton sarong, with checked patterns printed in pastel colours, was also popular with early English rubber planters as it provided cool respite from the overbearing tropical heat.

During other times, some western-influenced Babas showed preference for waistcoats with brass buttons, while others sported bow ties. The standard outfit for a Straits Chinese office worker during the first half of the 20th century was a white cotton shirt, trousers, European leather shoes and a straw hat.

Nyonyas, on the other hand, rarely followed Western styles. Although, occasionally, women from affluent Peranakan families wore European gowns and dresses to symbolise their social status.

The daughter of a wealthy Baba entertaining European guests with an after-dinner piano or violin recital would likely dress herself in a western evening dress to suit the prevailing style around her.

NYONYA COSTUMES

Apart from those rare occasions, Peranakan ladies were more inclined toward Malay dressing styles. Their basic attire was the sarong, which was often matched with various blouse types as a two-piece ensemble.

Popular among the older generation was the baju panjang, which closely resembled the Malay baju kurung.

Widely considered the original traditional Nyonya costume, it consisted of a long-sleeved tunic worn over a colourful sarong, which was usually imported from Pekalongan, a renowned textile manufacturing town on the north coast of Java.

Usually hand-stitched, but sometimes made with the help of sewing machines, the ends of the sleeves were purposely tapered to facilitate eating with fingers and also to show off gold ornaments like bangles worn on the wrists.

The baju panjang, which enjoyed widespread popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was held in place by a trio of brooches, or kerongsang in Malay.

Materials used to make baju panjang varied according to the fashion of the time. Early tunics made of cotton gingham were in vogue around the turn of the 20th century. Also referred to as Bugis cloth as they were produced in the Celebes (now Sulawesi), the fabric colours were sombre, ranging from grey to ochres and earthy reds.

Nothing is permanent, especially when it comes to dressing style.

While comparing several eye-catching vintage photographs in my collection that feature different Straits Chinese dressing styles, it becomes evident that factory-milled textiles from Europe began making their appearance in Malaya around 1910.

EUROPEAN FABRIC GAINS POPULARITY

Not long after, the Bugis cloth gradually gave way to French and Swiss voile fabric that featured superior white thread embroidery. Referred to as lace cloth by female Peranakan of Hokkien descent, the attractive material was made interesting with popular motifs like flowers, butterflies, bees and birds.

By the 1920s, German organdie in colourful prints that was all the rage in Europe at that time made its way to Malayan shores and became an overnight sensation among the Nyonyas.

Called German cloth by the Hokkiens, it featured bold floral designs superimposed on a background of white horizontal or vertical lines.

As these fashionable imported fabrics were thin and rather revealing, Nyonyas wore white cotton baju dalam under the tunics to protect their modesty.

Within the confines and privacy of their homes, Straits Chinese women merely wore this short undergarment with a sarong and only put the transparent tunic on top when they entertained guests at home or ventured out.

Towards the early 1930s, fashion once again evolved and Nyonyas began favouring shorter body-hugging kebaya made of embroidered robia voile fabric worn over cotton camisoles. Paired with the ever versatile sarong, this dress style called baju Nyonya quickly became the accepted daily wear.

The earliest Nyonya kebaya was not embroidered, but instead edged with broad lace. This form of fabric accentuation is believed to have come from Portuguese and Dutch influences. Despite their overall similarity in terms of shape and design, there are distinct differences between the kebaya worn by Malays and Nyonyas.

The Malay kebaya is usually knee length and made of cotton or silk, while Straits Chinese women favoured shorter versions that used embroidered sheer fabric.

Thanks to their enduring appeal and timeless elegance, both forms of kebaya dresses have remained popular through the years and are still very much in fashion to this day.

Source: NST